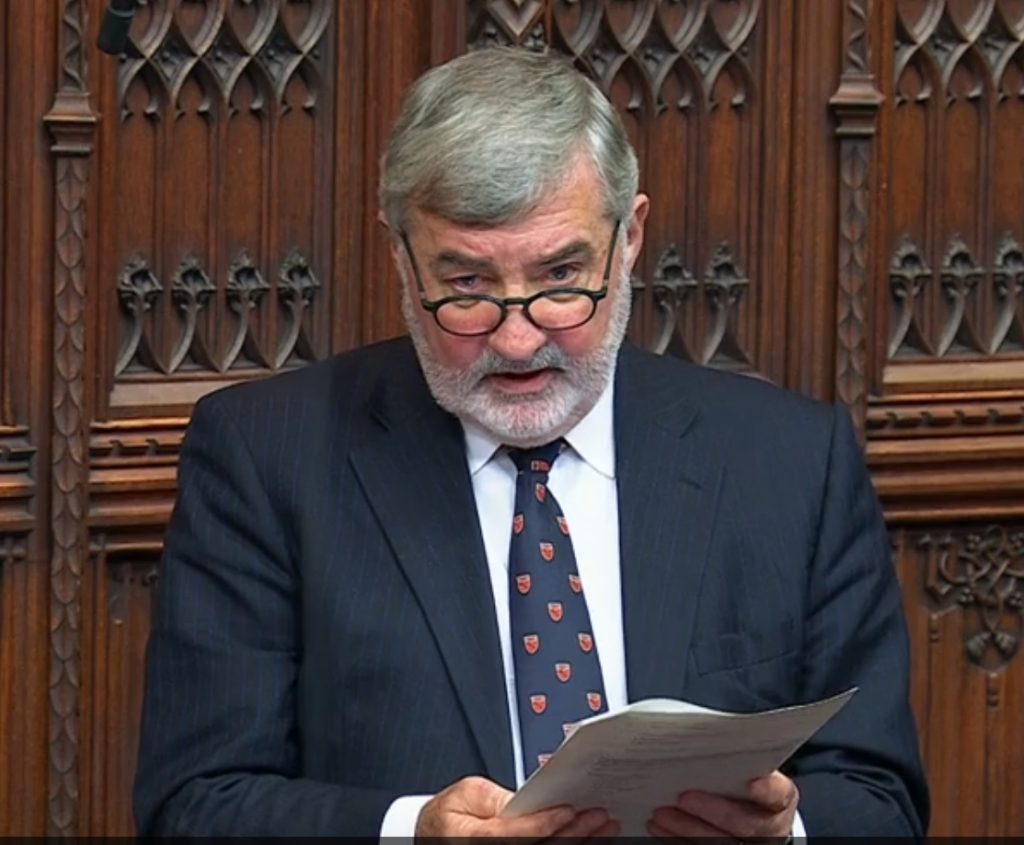

Lord Alderdice, speaking in the House of Lords on Thursday 21 November 2024 on the motion moved by Lord Ricketts “That this House takes note of the Report from the European Affairs Committee The Ukraine Effect: The impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on the UK-EU relationship (1st Report, Session 2023-24, HL Paper 48)”

Lord Alderdice said – “My Lords, I start my comments by identifying with the tribute and appreciation paid by the noble Baroness, Lady Helic, to the noble Lord, Lord Levene of Portsoken. He has been a great public servant, and that is the best that can be said of any of us in your Lordships’ House. I also congratulate the noble Lord, Lord Ricketts, and his impressively experienced committee and welcome this report as a thoughtful and informed contribution to a crucial conversation about relations with our nearest neighbours in the context of the Russia-Ukraine war. However, as he and others have rightly said, the situation has moved on considerably since the completion of the report, and even in the past couple of days.

I am not sanguine about sanctions, the defence capacity of the EU and a geopolitical transition that is disadvantageous for the UK.

Paragraph 86 of the report says that that one of the witnesses noted “that sanctions are a coercive measure, and their primary aim is to change behaviour”. In paragraph 104, the Foreign Secretary of the time, the noble Lord, Lord Cameron of Chipping Norton, is noted as having suggested “that the arrangements for cooperation between the UK, the EU and other allies on sanctions … have been effective in responding to the crisis in Ukraine”. One measure of effectiveness is how well the UK and the EU have co-operated on developing a sanctions regime. There has been some progress, although in response to the acute crisis of a war it seems to go at a rather sluggish pace more suited to a time of peace. A different measure of effectiveness would be how far it has modified Russian behaviour. If the purpose was to bring the war to an end in Ukraine’s favour, it seems that sanctions have not been very effective, but they have deepened the global division between the G7 and our other allies and the growing community of BRICS and their allies. The global economic landscape has shifted dramatically in recent years. In 1992 the G7 accounted for some 45% of global GDP against the BRICS countries’ less than 17%. However, by 2023, the BRICS bloc accounted for 37% of global GDP, compared to the G7’s 29%. This is not a development likely to impact President Putin’s behaviour in ways that are helpful to us and Ukraine.

On the more immediate defence issues, the picture is perhaps even more troubling. As noted in paragraph 117, we can take some pride that the UK has been important in

“normalising the provision of certain weapons systems early on”, pushing out “the boundaries of what is possible” and providing “some leadership in allowing a debate to be had about particular weapons systems”. While eventually and belatedly President Biden has permitted ATACMS to be used directly in Russian territory against Russian aggression, our German friends remain resistant to provide the Taurus missiles that could make a significant difference.

The report points out that the EU, with its population and resources, ought to have the potential to produce and sustain a substantial defence against Russian aggression. However, even after years of our US ally—and some of us in this House—warning of the imperative for Europe to shoulder the burden of its own defence, there is an almost universal recognition that the EU is not a sufficient defence pillar, as evidenced by the PESCO initiative, for example, being so slow to get up and running despite having been on the agenda for years. In truth, our defence at this point remains dependent not on our EU relations but on NATO. Without an enthusiastically committed US pillar to NATO, we would not be able to sustain the resourcing for Ukraine and, as the report says, Europe is

“lagging behind Russia’s ongoing efforts to prepare and provide for the long war that is probably ahead of us”.

Concerns about the incoming Trump presidency and a likely “dramatic change of US policy” have resulted in many meetings and press column inches in Europe, but they do not yet seem to have galvanised the EU into sufficient production and action, and while the UK has taken the lead in some senses, recent reports about £0.5 billion of savings being demanded by the Treasury send the wrong signal to Russia and her allies. It all seems to show a lack of appreciation of the gravity of the situation we face, quite possibly for much of the lifetime of those participating in this debate. I ask the Minister to clarify for us as much as she can what the situation is with these reports of cuts.

I have not said anything about reconstruction because I cannot see how Governments, never mind the private sector, can be persuaded to espouse in practice the injunction in paragraph 192 of the report that: “Reconstruction cannot wait until the war has finished”. Many will take the view that it is unwise to spend resources on reconstruction that will be destroyed, rather than on the weapons needed to bring the war to a satisfactory end.

In addition, as noted in paragraph 215, reconstruction is expected to be linked closely to Ukraine’s candidacy for EU membership, and it is difficult to see how this country is able to do much to facilitate this long-term ambition for Ukraine when we have so recently departed the EU ourselves and are not at the table. Perhaps even more significantly, our departure hardly makes us the best people to recommend and facilitate Ukraine’s entry into the EU.

In any case, as the report says, NATO is the critical actor in providing Ukraine with long-term security, not so much the EU, and that should perhaps be our focus from a security and indeed a foreign policy perspective. NATO membership is more likely to be the solution to the defence of Ukraine and will ultimately provide the context for its reconstruction, as the EU remains divided over aspects of its response to the conflict, not least the impact of the decisions of Hungary and Slovakia. More widely, the EU’s problems in establishing a clear agreed geopolitical role, whether in response to the conflict in Israel, Gaza and the wider Middle East or relations with China, reflect additional divisions between EU member states compared to their response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

At this stage in the Russia-Ukraine war, one could have hoped for and expected a more impressive and impactful response from our relationship with the EU. I am disappointed that we still seem to await such a development and I look to the Minister to give us some encouragement that we can expect more in the upcoming year.